Second Inaugural Address: Editorial Note

Second Inaugural Address

- i. topics for inaugural address, [before 8 feb. 1805]

- ii. partial draft, [before 8 feb. 1805]

- iii. partial draft, [before 8 feb. 1805]

- iv. partial draft, [before 8 feb. 1805]

- v. partial draft, [before 8 feb. 1805]

- vi. partial draft, [before 8 feb. 1805]

- vii. james madison’s remarks on a draft, [8 feb. 1805]

- viii. albert gallatin’s remarks on a draft, [12 feb. 1805]

- ix. from henry dearborn, [13 feb. 1805]

- x. to robert smith, 14 feb. 1805

- xi. james madison’s remarks on a draft, [21 feb. 1805]

- xii. notes on the second inaugural address, [february 1805?]

- xiii. second inaugural address, [before 4 mch. 1805]

- xiv. reading copy of second inaugural address, [before 4 mch. 1805]

- xv. to samuel harrison smith, [ca. 4 mch. 1805]

EDITORIAL NOTE

Before noon on Monday, the 4th of March, Jefferson mounted his horse—probably Wildair, his prized bay saddle horse—and rode the mile and a half up Pennsylvania Avenue from the President’s House to the Capitol. Augustus John Foster, the 24-year-old secretary of the British legation in Washington, left a record of the details he observed on that day. The president, who “affects great plainness of dress and manners,” was dressed all in black, including silk stockings, and was “attended by his secretary and groom.” The secretary was Isaac A. Coles, the young Virginian from Albemarle County who, since December, had been filling in for William A. Burwell as Jefferson’s private secretary. Jack Shorter, an enslaved stable hand at the President’s House, may have been the groom. At the Capitol, “a mixed assemblage of Senators, Populace, Representatives, and ladies” gathered in the Senate chamber. Members of the foreign diplomatic corps were also present. Among the observers in the gallery was the outgoing vice president, Aaron Burr, who had been dropped from the ticket for Jefferson’s second term. Absent from the scene were some members of Congress who had left for home after the close of the session the previous day (Augustus Foster to Frederick Foster, 1 July 1805, in Vere Foster, ed., The Two Duchesses: Georgiana Duchess of Devonshire, Elizabeth Duchess of Devonshire [London, 1898], 229-30; Richard B. Davis, ed., Jeffersonian America: Notes on the United States of America Collected in the Years 1805-6-7 and 11-12 by Sir Augustus John Foster, Bart. [San Marino, Calif., 1954], 15; John Quincy Adams, diary 27 [1 Jan. 1803 to 4 Aug. 1809], 149, in MHi: Adams Family Papers; , 315; Lucia Stanton, “Those Who Labor for My Happiness”: Slavery at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello [Charlottesville, 2012], 49; , 2:1034; Vol. 32:400-1, 540; Vol. 40:59).

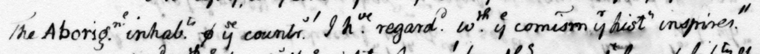

To deliver his inaugural address, Jefferson had prepared a special reading copy that is unlike any other document in his papers (see Document XIV below and illustration in this volume). By abbreviating most words, even short ones, he compressed the full text of the address, more than 2,100 words in 15 paragraphs, onto the two sides of a single sheet of paper about 9¾ inches wide by 16¾ inches long. He ended each line at the close of a sentence or clause and used indents to set off topics and subtopics. He employed standard techniques of abbreviation, including superscripted letters and macrons or tildes above the text (not reproduced in the transcription of Document XIV). To achieve maximum efficiency of space along the line, he sometimes placed a superscripted letter directly above another letter. In some cases he used two levels of superscription in one abbreviation (as in “Aborig.n.l” in the detail seen below). For the word “of,” rather than superscripting the f above the o, he superimposed the two letters to create what is in effect a compact symbol rather than a simple abbreviation. Drawing on earlier scribal practice that was falling out of use by 1805, he employed the letter y to stand in for the Old English thorn and represent th at the start of a word. The result in the reading copy, in combination with his persistent use of abbreviations, is not just “ye” for “the,” but “ym” for “them,” “yse” for “these,” “ys” for “this,” “yt” for “that.” In a departure from this edition’s usual practice of transcribing a y-for-thorn as “th,” the y has been retained in Document XIV. Jefferson used a dot, slightly heavier than a period and placed slightly below the line, to stand in for the letter o in words such as “to” and “no.” When directly below the letter, the dot represented the vowel sound in a word such as “too” or “who.” A superscripted dot was the letter e for words such as “be” and “we”; a dot very slightly above the line was the letter y in “by”; and a dot directly above a letter stood in for the “ay” or “ey” of “may” and “they.” Regardless of Jefferson’s placement of the dots, all are rendered as periods on the line in the Document XIV transcription.

With these techniques, Jefferson rendered the sentence “The Aboriginal inhabitants of these countries I have regarded with the commiseration their history inspires” as:

The sentence “I have therefore undertaken, on no occasion, to prescribe the religious exercises suited to it” appears as:

And “they too have their Anti-Philosophists, who find an interest” he copied as:

Visible in those examples are additional markings that do not represent letters of the alphabet. They are diacritical marks to assist Jefferson in the oral delivery of the address. In each of the segments illustrated above, a single long stroke appears in a high position midway along the line. At the end of a line, as seen in the first two details shown above, he put a double stroke or a third mark in the form of a long cross or dagger. These marks were Jefferson’s cues for pauses as he read the address. They resemble marks that Jefferson put on a draft of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Julian Boyd linked the markings on that early version of the Declaration to the marks present in this reading script. Boyd interpreted the marks as indicators for accented syllables and emphasis in reading, similar to linguistic accents that Jefferson had pondered in his 1786 essay on English prosody (see Vol. 10:498n). In a later reading of the marks, Jay Fliegelman instead asserted that, based on the placement and appearance of the markings, they represented not accented syllables but “rhythmical pauses of emphatical stress” used to “divide the piece into units comparable to musical bars or poetic lines” (Julian P. Boyd, “The Declaration of Independence: The Mystery of the Lost Original,” , 100 [1976], 460; Jay Fliegelman, Jefferson, Natural Language, & the Culture of Performance [Stanford, Calif., 1993], 5-7, 10).

The marks are nearly identical to those recommended by Irish actor, speaker, and rhetorician Thomas Sheridan, whom Jefferson occasionally recommended to young scholars seeking reading lists. Sheridan had turned from acting to a career of public lectures and writing in 1756, becoming a key driver of an elocutionary movement that centered performance at the heart of all public speaking. He was well known for his highly disciplined acting preparation, which informed his later works on elocution, speaking, education, and the English language. Jefferson had apparently owned a copy of Sheridan’s 1762 Lectures on Elocution before he loaned it out in the 1760s; he later filled the void in his library with a 1787 reprint. In that work, Sheridan lamented the shortcomings of English grammar, the markings of which “are by no means fitted to the natural rests and pauses of discourse” and have “proved the chief cause of some of our greatest imperfections in reading.” Adequate stops allowed the speaker to breathe and rest and allowed the audience to fully understand the message. The speaker could also add weight to the most essential elements of an oration by using well-placed pauses, thus allowing those points to “sink deeper” into the mind “by such reflection” (; William Benzie, The Dublin Orator: Thomas Sheridan’s Influence on Eighteenth-Century Rhetoric and Belles Letters [Menston, Yorkshire, 1972], 114; Thomas Sheridan, A Course of Lectures on Elocution Together with Two Dissertations on Language and Some Other Tracts Relative to Those Subjects [1762; reprint, London, 1787], 13, 94, 97; No. 4655; , 1:576; 7:629; Vol. 30:594; Vol. 32:180; TJ to John Page, 17 Apr. 1767 [RC, University Archives, Westport, Conn., 2017]; Samuel R. Demaree to TJ, 28 Dec. 1804).

While Sheridan outlined the necessity of pauses in the earlier work, he detailed the mark-up system in his 1775 Lectures on Reading. He implemented four different marks for pauses: a single prime for “the shortest pause marking an incomplete sense,” a double prime for “double the time of the former,” three prime marks for a full stop, and two horizontal lines to mark a pause “longer than any belonging to the usual stops.” It is unclear when or where Jefferson read Lectures on Reading prior to drafting the Declaration of Independence, and no copies of the work are included in his library catalogues. He did possess a 1781 edition of Sheridan’s Rhetorical Grammar of the English Language, which also detailed the mark-up system. Jefferson incorporated Sheridan’s prime and double prime marks, the single marks frequently appearing mid-sentence and the double primes marking longer breaks or sentence endings. The reading script also separates topics and incorporates longer pauses by supplying line breaks and section indents. Instead of using Sheridan’s triple prime or horizontal line markings, Jefferson substituted the dagger, which likely signaled a longer emphatical break (Sheridan, Lectures on the Art of Reading [London, 1775], pt. 1, 181-2; Sheridan, A Rhetorical Grammar of the English Language [Dublin, 1781]; No. 4847).

Jefferson’s painstaking work in preparing the reading copy was worthwhile in allowing him to put the full text of the speech on the two faces of the single sheet. Yet for all the effort and thought he invested in making the copy a script for oral delivery, as an oration the address failed. He spoke, according to John Quincy Adams, “in so low a voice that not half of it was heard by any part of the crowded auditory.” Augustus Foster also noted that the speech was “too low spoken to be heard well.” The inflections carefully marked according to Sheridan’s principles came to nothing.

On finishing the address, Jefferson kissed the Bible, swore the oath of office administered by Chief Justice John Marshall, and bowed. He then returned to the President’s House, where according to Foster he was in “high spirits” as “everyone by common accord went to pay him a visit of congratulation.” The 8 Mch. Aurora described the gathering as “thronged with people, so that the avenues and hall were scarcely passable.” Adams, who only stayed about half an hour before returning home to spend the remainder of the day writing at his desk, missed the latter part of the levee at the President’s House. Foster, an English baronet and career diplomat, took pains to note the presence of the “blacks and dirty boys, who drank his wines and lolled upon his couches before us all; the jingling of a few pipes and drums finished the day. There was nothing dignified in the whole affair.” Foster gave scant notice (and Adams none) to another event that marked the day, a procession of skilled artisans and workers from the Washington Navy Yard. “There was a collection of people in procession on the road,” Foster observed, “but they seemed composed of low persons, for the most part Irish labourers, and appeared very cheerless.” He declared that “Unbounded freedom reigns in this unbounded land” (Foster, Two Duchesses, 229-30; Davis, Jeffersonian America, 15; Adams, diary 27 [1 Jan. 1803 to 4 Aug. 1809], 149, in MHi: Adams Family Papers; National Intelligencer, 6 Mch.).

Jefferson had begun writing the address weeks earlier. When he started is not known, as he did not put dates on any of the surviving draft fragments. He apparently had a complete draft by 8 Feb., for on that day he received James Madison’s response, followed on the 12th by remarks from Albert Gallatin and from Henry Dearborn the following day. Jefferson asked for comments from Robert Smith on 14 Feb., and received a second set of notes from Madison on the 21st. Sometime between that date and 4 Mch. the address took final form. (See Documents vii-xi for the review of the address by the members of the cabinet.) The versions of the text reviewed by Jefferson’s advisers are not extant in his papers. No full text of the address previous to its finished state as he delivered it on 4 Mch. has been found. Yet several fragments of his drafting process have survived (Documents i-vi below). Their association with the second inaugural address is based on inference, as none of them is so labeled. Three of them, which are treated as separate texts below (Documents I, III, and V) are on the two sides of a leaf of paper that for a time was filed in Jefferson’s papers in the Library of Congress with manuscripts from the fall of 1776 concerning the disestablishment of the Church of England in Virginia (see Vol. 1:528). Another piece from his drafting of the second inaugural address is on the same sheet as fragments of text from Jefferson’s early drafting of his first and third annual messages to Congress in 1801 and 1803 (Document II).

Neither of Jefferson’s predecessors as president had given a second inaugural address. George Washington had chosen to speak only briefly, and John Adams had not had the opportunity to give one. In a document that he wrote after he completed the drafting of the address and headed “Notes on a Draught for a second inaugural Address” (Document XII), Jefferson commented on the differing functions of his first and second inaugural speeches. “The former one was an exposition of the principles on which I thought it my duty to administer the government,” he wrote. His second inaugural address “then should naturally be a Compte rendu, or a statement of facts, shewing that I have conformed to those principles. the former was promise: this is performance.” He continued: “yet the nature of the occasion requires that detail should be avoided; that the most prominent heads only should be selected, and these placed in a strong light but in as few words as possible” (, Pres. Ser., 12:264-5; Document XII).

At the outset of his drafting process, he identified those “most prominent heads” for the address in a spare outline that listed four “Genl. topics” (general topics): “the advantages of a peaceful system” that made possible a favorable state of public finances in which the country had the ability to pay off its debts and eliminate internal taxes; “removals from office”; a third topic that he named only as “Philosophy”; and finally “licentiousness of press” (see Document I). The address in its final form included additional topics, such as religion, Native Americans, and Louisiana. The four original “Genl. topics”—or five, taking “the advantages of a peaceful system” to mean foreign affairs—were the ones that Jefferson initially identified as the core of the address.

Using a process that he had come to employ in composing his annual messages to Congress, he proceeded to draft each of the topical sections independently. Two of those pieces can be identified and are Documents II and III below. Document IV was his first attempt to bring the elements together. Although incomplete and still preliminary, consisting of a compilation of notes rather than finished text, it is the fullest version that remains from the drafting process. For some topics, such as religion and Louisiana, the document contains only a heading to serve as a placeholder. Document IV illustrates, with Documents II and III, the mechanics of Jefferson’s process as he worked out the sequence of parts to assemble the address. Combinations of numbers and letters in the margins of the draft fragments, “h. 11.” on Document II and “4. e.” on Document III, correlate with similar markings in the margins of Document IV. Jefferson probably first used numbers to identify the topics, as the numbers in the margins of Document IV are in order, beginning with 2 and running through 8. (The “11” on Document II suggests that Document IV originally had an additional page that has not been discovered.) The numbers served as keys for those parts that were on separate pieces of paper. Jefferson then decided on the order of the topics for the address and used letters, which he added alongside the numbers, to identify the desired sequence. The paragraph in Document II, originally labeled as “11,” became “h,” and the paragraph on religion in Document III changed from “4” to “e.” The part originally numbered as “8” in Document IV he designated as “a,” to be the first in the sequence, and it did become the opening passage of the address: “Proceeding f. c. to that qualificn which the constn requires before my entrance on the charge which has been again conferred on me” (compare the opening of the finished address, Document XIII).

Documents V and VI are probably from a later stage, subsequent to the sorting out of topics seen in Documents ii-iv. The margins of Document V (which is on the same manuscript sheet as Documents I and III) and Document VI lack the numbers and letters that Jefferson used to key each of the earlier pieces to its place in the sequence. These documents appear to be efforts to work out expressions of ideas and particular phrasings. This is particularly true of Document VI, in which he labored to find the language he wanted for one paragraph of the address. Using both sides of his page, he made a heavily altered draft and then rewrote it. Some phrasing from the revised version of the passage found its way directly into the final state of the inaugural address, such as “think as they think, and desire what they desire.”

Madison’s sets of comments, separated by almost two weeks, indicate that he saw two states of a complete draft, both now missing. The first full text that survives is the finished address, Document XIII below. In its development, the subjects that followed the straightest path from Jefferson’s first bare outline of “Genl. topics” to the fully realized address were the ones that he had combined as the first item in Document I: “the advantages of a peaceful system. that if once our debt is paid & taxes liberated, the surplus (after supportg. govmt) will supply annual exp. of war so that no other tax need ever be laid.” The theme of having the benefit of a sufficient revenue even with the elimination of internal taxes he carried through the drafting process to the finished address. By contrast, the next item in the “Genl. topics” outline, which he listed as “removals from office,” almost disappeared. In the outline he likely intended to use the subject of “removals from office” to talk about politics by arguing that he could have removed more officeholders and eliminated more offices than he had. In the end, the topic survived in the address only in the form of a passing reference to a reduction in the number of government offices as a factor in the lessening of expenditures. Topics that he had not included in the original sketch outline but introduced early in the drafting process, including religion and Louisiana, carried through to the finished address after scrutiny by the members of the cabinet.

Jefferson struggled with the two additional “Genl. topics” that appear in Document I, “Philosophy” and “licentiousness of press.” When he wrote in the “Notes on a Draught for a second inaugural Address” that the speech would center on his fulfillment of the principles on which he had been elected in 1801 (Document XII), he did not have in mind a simple tallying of his administration’s successes. He was, rather, judging from the results and from what we can see of the drafting process, intent on explaining himself in the face of persistent political opposition. By “Philosophy” he meant reasoned thought and rational inquiry—what we might characterize as Enlightenment thinking. Prior to his election as president, he had railed against statements by Federalists, including John Adams, who appeared to scorn innovation and declare, in Jefferson’s paraphrasing, that “it is not probable that any thing better will be discovered than what was known to our fathers” (Vol. 31:128-9). His political opponents perpetually decried him in print as a “philosopher” and one who had no respect for the established order of things. Why he would feel such a need in March 1805 to respond to that current is not clear. In the “Notes on a Draught,” he gave the issue acute importance, stating that “every respecter of science, every friend to political reformation must have observed with indignation the hue & cry raised against philosophy, & the rights of man.” He saw a danger that philosophy and natural rights “would be overborne, & barbarism, bigotry & despotism would recover the ground they have lost by the advance of the public understanding.” He felt it was important to say something about the “anti-social doctrines,” yet “not to commit myself in direct warfare on them” (Document XII). His solution was to discuss the topic only in reference to Native American society. In the address, the “Anti-Philosophists” who opposed innovative thinking and clung to “a sanctimonious reverence for the customs of their ancestors” were Indians opposed to progress and change (Document XIII).

His purpose in writing the “Notes on a Draught” was to explain his handling of this topic. He likely meant the undated “Notes,” written sometime after he had finished writing the address, to be part of his personal record of the politics of his era. If so, the document has kinship to his January 1804 notes of conversations with Aaron Burr and Benjamin Hichborn (Vol. 42:226-7, 346-9) and other personal memorandums on political topics, including his notes from the time of George Washington’s cabinet that Thomas Jefferson Randolph named the “Anas” (, 4:443-523). Recognizing that his treatment of the topic of “Philosophy” in the address was unorthodox, he apparently wrote the “Notes on a Draught for a second inaugural Address” to memorialize the decision for his ongoing record of his own times.

He made the decision during the drafting process, as shown by Madison’s and Gallatin’s remarks, for in the draft they saw, resistance to change was associated with Native American society (Documents vii-viii). When Jefferson created Document IV, his initial assembly of pieces of the draft, he included brief notes on three published works: in Marco Lastri’s Corso di agricoltura he found remarks on innovation and improvements in agriculture; from the Comte de Ségur’s History of the Principal Events of the Reign of Frederic William II he took an extract on resistance of the Catholic Church to new knowledge; and from David Williams’s Claims of Literature he made notations “that science disqualifies men for the direction of the public affairs of the nation is one of the artful dogmas of ignorance & bigotry” and about “the action & counteraction of knolege & ignorance.” Jefferson’s notes from Williams’s book also included references relating to the response to be made by a government to criticism, which connects to his “licentiousness of press” topic, and so it is not certain if Jefferson, as he worked on Document IV, had yet determined to limit his remarks on “Philosophy” to the section on Native Americans. He had at least made a decision to discuss innovation and change in that part of the address. Immediately below the reading notes in Document IV he drafted a piece (“3. f.”) that he did not label as pertaining to Indians but which surely did, for in it he framed innovation in terms of eating acorns instead of embracing the “innovation of bread” and he mentioned resistance to technology such as mills and plows. He used a phrase taken from his notes on Williams’s book just above: “counteraction of knolege & ignorance.” He also used wording that appeared in modified form in the part of the finished address relating to Native Americans, including “a sanctimonious reverence for antient & steady habits” and “they too have their Antiphilosophists.” He made at least a beginning, by Document IV, of latching the topic of “Philosophy” to his comments about native peoples.

The expression “steady habits” is associated with the state of Connecticut. Jefferson’s use of it signals that in Document IV he was at least experimenting with the idea of using Native Americans as proxies for comments about Federalists’ opposition to his ways of thinking. He considered Connecticut to be the strongest holdout against Democratic-Republican principles (see for example his letter to William Heath of 13 Dec. 1804). “Steady habits” or some variant of the phrase was in the draft that he first circulated to the members of the cabinet, as shown by a remark by Gallatin on the section on Indians: “the allusion to old school doctrines & to New England habits appears to me inexpedient” (Document VIII). Gallatin was baffled by the inclusion of a discussion of innovation and resistance to change in that section of the address. Jefferson stuck to his intention to make “Philosophy” a topic in the address and to make the section on Indians the platform for it. But he altered the phrase that had pointed to New England, and in the end disguised his purpose.

Jefferson also struggled and held firm to another of the topics first marked for discussion, the “licentiousness” of the press. He did not use that word in Document IV, but it is in the finished address (Document XIII). In Document IV he first applied another term, the “artillery of the press,” and he unleashed his own barrage, a salvo of words: “malice,” “treason,” “calumnies,” “falsehood & defamation.” Jefferson regularly received aggressive press attacks from the Federalists, and it is impossible to pinpoint a single trigger for his evident anger in this section. The New-England Palladium had leveled a front page series of attacks on him in January, which had caused quite a stir and likely remained on his mind during the drafting process. He had struggled with the role of the press throughout his presidency, and his drafting process reveals the competing notions of the press as a tool for government accountability or as a forum for divisive misinformation (New-England Palladium, 18 Jan.; Isaac Story to TJ, 8 Feb.)

Jefferson acknowledged that public officials need oversight. In the drafting process, he struggled with how to best express this, referring first to a “Censor on the public functionaries” that, writing with freedom, could warn “against deviations from the line of duty” (Document II), later to “watchmen over every branch of government,” (Document VI), and last to an opposition that would practice “censorial functions” (see the second part of Document VI). In Documents II and VI, Jefferson implied that the role of censor on government could be played either by the people at large, who monitor public officials by thinking freely and voting accordingly, or by the press, which could print the truth and hold public officials accountable. Carrying through the full drafting process is Jefferson’s belief that the press violated its sacred duty as a watchman by attacking Jefferson’s person and administration. In Document II, this is “violations of truth and decency.” In Document IV, he detailed the printing of “every thing which malice could inspire, fancy invent, falshood advance, & ridicule and insolence dare,” which could undermine the confidence of the people in their government.

Printers, Jefferson argued, needed to be held accountable for disseminating dishonest or licentious information. Leonard Levy’s 1963 critical interpretation of the president, Jefferson and Civil Liberties: The Darker Side, laid out the development of Jefferson’s thought process on printing and freedom. Levy tied Jefferson’s beliefs to an English or common-law interpretation of press freedom, in which printers were free from advance censorship or licensing acts but could be prosecuted after the fact for abusing that freedom to express seditious libels, licentious opinions, or malicious falsehoods. That philosophy held strong in the second inaugural, where Jefferson seemed to admit that the press should be free from prior restriction, but held accountable by state laws (mentioned in Documents II, IV, and XIII) and public indignation (Documents II, IV, VI, and XIII). Jefferson had long struggled with opposition. According to Levy, Jefferson’s “threshold of tolerance for hateful political ideas was less than generous.” He would rhetorically defend free speech, but “in favor of the liberty of his own political allies or merely in abstract propositions,” while in practice “he found it easy to make exceptions when the freedom of his enemies was at stake.” By 1805 this view already contrasted with that held by a growing number of members of his own party, who embraced a newer libertarian ethos that opposed prosecutions for seditious libel, only supporting libel and slander prosecutions to protect the reputations of private individuals against malicious falsehoods (Leonard W. Levy, Jefferson and Civil Liberties: The Darker Side [Cambridge, Mass., 1963; reprint, Chicago, 1989], 44, 49, 51-3).

Seemingly in line with that new ethos of free speech, in Document IV Jefferson indicated that he had intentionally allowed for the press to be completely unshackled—even largely from state-level reprisal—as an experiment to see whether “freedom of discussion” could be “sufficient for the propagation & protection of truth,” and whether the government, “conducting itself with fidelity & zeal,” could be defeated by printed “falsehoods & atrocities.” In Document XIII, he admitted that “public duties more urgent press on the time of public servants,” leaving offenders “to find their punishment in the public indignation.” But he kept most of the language about an honest government and an experiment in free speech.

By the time he drafted Document IV, Jefferson had settled on the voting public holding the role of watchman over both the public officials and the press. In Document II, he first expressed that with an “enlightened & just estimate,” the people can consign the licentious presses “to oblivion.” In Document IV he expanded this, writing that the public, by remaining “cool & collected” and seeing through the “falsehoods & atrocities,” could hold the press accountable by endorsing embattled public officials through the medium of elections. The credit to the people for resisting the machinations of the press carried into the final version (Document XIII), where he retained the language about his “cool, & collected” fellow citizens holding the press accountable with the “Censorship of Public Opinion.” Of course, he clarified that he still thought that “the laws provided by the states against false & defamatory publications” should be enforced.

The concept of a public censor on government was largely downplayed in the final draft, where Jefferson instead lauded his “fellow citizens” who, “by the weight of public opinion, influence and strengthen the public measures.” Carrying through the majority of the drafting process was Jefferson’s unwavering faith in the people for reelecting him, ultimately granting vindication to his administration. He continued to use the idea of a national “union of sentiment” to depict hardened opposition as an anomaly and the worst Federalist printers as a numerically small holdout of false and backwards thought. His reelection proved that the majority of American citizens supported the administration’s actions and remained immune to licentious printers’ influence.

Gallatin took issue with the presentation of the press in the draft he reviewed (see Document VIII). He suggested that it would be preferable to “suppress all which may be considered as expressions of personal feelings,” although he did agree that press dishonesty and “licentiousness” lessened journalism’s usefulness to society. The section on the press, he informed the president, was “susceptible of improvement.” Despite Gallatin’s comments, Jefferson kept his attack on the “artillery of the press,” but incorporated Gallatin’s caution to shy away from personal feelings, instead accusing the press of attacking “us,” the administration and the “union of sentiment” as a whole (Document XIII).

When he had the address in the form he wanted, Jefferson used his polygraph to help him make multiple copies and submitted the final text to Samuel Harrison Smith for printing. Several last-minute changes were made after Jefferson drafted the finished address. Many were incorporated into Smith’s copy, and others were added to both copies via editorial marks. Even with the corrections, Jefferson continued adjusting the address until the eleventh hour, submitting a few changes to Smith after he sent along the full draft (see Document XV). Jefferson had the copy for publication in Smith’s hands early enough for it to be published in the National Intelligencer as a supplement on 4 Mch., the day on which the address was given. It occupied the front page two days later and was published in Smith’s Universal Gazette on 7 Mch.

The address rapidly circulated through the states after Smith’s printing, with many newspapers publishing the speech in full. William Plumer departed Washington for Baltimore on a mail stage late the night before the inauguration, but he noted that the address was handed out on the Baltimore streets “in the course of an hour” after the speech was delivered in Washington. “I have no doubt,” he wrote, “that it was printed long before I left Washington & was bro’t to Baltimore in the same stage that brought me.” The American, and Commercial Daily Advertiser of Baltimore printed the speech in full on the 5th, with the editor noting that the print had reached the Baltimore office by a late night express, allowing the editors to “experience a peculiar satisfaction, in being enabled, by anticipating the mail, thus early to present it to their numerous patrons.” The full address was printed in the Alexandria Expositor on 6 Mch., with the printer explaining that they already distributed the speech as a handbill but included it in the newspaper “for the benefit of our country subscribers.” The Washington Federalist also printed the address on the 6th. It took slightly more than two weeks for the address to travel up and down the east coast. It had reached Relfs Philadelphia Gazette by the 7th, the Enquirer of Richmond and the Republican Advocate of Fredericktown, Maryland, by the 8th, the Mirror of the Times of Wilmington and the Richmond Virginia Gazette by the 9th, the Boston Independent Chronicle on the 14th, the Charleston City Gazette and Daily Advertiser on the 15th, and the Eastern Argus of Portland on the 22nd. The Boston Democrat filled the front page of the 16 Mch. paper with the address and also advertised the sale of a broadside printed on white satin. It was printed in German in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, on the 23rd, and had reached the Louisiana Gazette by 12 Apr. (Noble E. Cunningham, Jr., The Inaugural Addresses of President Thomas Jefferson, 1801 and 1805 [Columbia, Mo., 2001], 89-90; , 315).

While some printers were content to reproduce the address with minimal commentary, a number of local editorials—Republican and Federalist—wrapped the text in either praise or condemnation, usually in line with the paper’s party affiliation. In the 6 Mch. National Intelligencer, Samuel Harrison Smith praised the address for announcing “the continuance of those pure principles of republicanism, which four years ago recommended Thomas Jefferson to the suffrages of a free people.” Extolling Jefferson for abusing “none of the powers which this confidence conferred,” Smith lauded Jefferson’s sentiments, which were in “the cause of human rights, and for the dignity of human nature, convictions of the superiority of republican over all other institutions.” The Alexandria Expositor of the same day accompanied the fully printed address with a summary and commentary on the key points, which praised Jefferson for “the application of sound practice” to achieve “the correct principles laid down” in his first inaugural address. The Worcester National Aegis of 20 Mch. commended Jefferson for directing the address to the “great body of the people.” It also supported Jefferson’s complaints about the press, adding a section on the “base and abominable slanders which have been belched forth against himself and his administration,” saying that in his remarks, the president “preserved the elevation of his character, while he expressed the honest indignation of his soul.”

The Alexandria Expositor picked up on Jefferson’s critique of the anti-philosophers in America, commenting on the “present state of the Indians,” among whom, the writer claimed, “are to be found the same sanctimonious attention to long established prejudices and unmeaning forms, the same dread of innovation and of reformation that has been employed so successfully to keep down the rising spirit of freedom in many of the European nations.” The article did not directly mention Federalists but leveled criticism at previous president John Adams, contrasting his visions for America with those of newly re-inaugurated Jefferson. The Fredericktown, Maryland, Republican Advocate likewise praised Jefferson and preceded the printed speech with a point-by-point summary, as “a more candid and affectionate Speech never fell from the lips of a public Magistrate” (8 Mch.). The National Aegis picked up on Jefferson’s jab at the Federalist Party in the section that purported to be about Native Americans. “We can scarcely conceive a more just and poignant satire on the haughty and unbending disciples of the ‘Old School’ among ourselves,” the editors wrote. They linked Jefferson’s anti-innovation comments directly to developments in New England, especially Connecticut, noting that “the same cowardly or designing policy, which fears or pretends to fear, danger in every change, prevails on the banks of the Connecticut and on the banks of the Ohio.” Pushing the analogy further, they argued that the Native American tomahawk “will be relinquished with as much reluctance as any relict of superstition, either of manners or religion, in a state of civilized society. The habits of savage life are as hard to eradicate, as the ‘steady habits’ enjoined by the Blue laws.” They called on the president’s opponents to read the address and take Jefferson’s principles to heart. The Republican Farmer of Danbury echoed that sentiment, saying that his rhetoric “applies so well to our Connecticut federalists, that some of them have suspected the President had them in his eye at the very time.” The editors argued that Indian “chiefs” and “powows” are “leagued together” like Connecticut officeholders and clergymen, stating that both “fear a change, not because the common people might suffer by it, but because they might lose their offices and influence.” They asserted that the “narrow and illiberal hatred to improvement and reformation, wherever it is prevalent, whether in the wigwam or the farmhouse, has a direct tendency to perpetuate barbarism, ignorance and tyranny” (3 Apr.).

On the other side of the political aisle, the New-York Evening Post attacked Jefferson’s references to his conscience and morality. The critical piece alleged that “in spite of all his bravadoes, he is an Hypocrite twelve hours out of the four-and-twenty.” The editors criticized Jefferson for giving a second inaugural address at all “without any precedent for it, and without any apparent reason but that of ingratiating himself with the people, and exhibiting a sort of defence against those severe but just animadversions which have been made upon his conduct.” The article picked apart Jefferson’s “conscience,” claiming that he improperly proclaimed his own justness, and lamented the “numbers of war-worn veterans who have been driven by him from their bread in the winter of life for their political principles” (20 Mch.). The Washington Federalist expressed similar sentiments, asserting that Jefferson chose not to make any new promises in this address as they “might again subject him to the inconvenience of having them contrasted with his actions.” The article condemned Jefferson’s claims to conscience and, like the Evening Post, attacked him for the dismissals of Federalists from offices. The editors also took issue with Jefferson’s tax section and particularly his claim that farmers, mechanics, and laborers would be free of taxation, “for it matters not to them, whether they give the money to the merchant who pays it to the tax-gatherer or to the tax-gatherer himself.” And, as frequently leveled at Jefferson, the Washington Federalist lambasted him for complaining about the licentious press in light of his former collaboration with James Callender (13 Mch.).

Personal reactions similarly adhered to party divisions. William Plumer accused Jefferson of hypocrisy: “his Conscience tells him he has on every occasion acted up to the declaration contained in his former inaugural speech. In that address he explicitly condemned political intolerance—declared all were federalists, all were republicans—Yet in a few days after that, he removed many deserving men from office, because they were federalists.” He also criticized Jefferson as imprudent for “explicitly censuring & condemning former Administrations & lavishing encomiums on himself for effecting a discontinuance of the Internal Revenues,” and for his expansive complaints about abuse by the press: “One would have thought that Mr. Jefferson after having hired such infamous wretches as Freneau, Bache, Duane, Callender, Payne & others, to defame villify & calumniate, Washington, Adams, & their associates—he would not have complained of news paper publications!” But even Plumer admitted that Jefferson “has his talents—& those of the popular kind,” since it was an important practice for him to “never pursue a measure if it becomes unpopular” (, 315-16).

John Tyler expressed the opposite view in a letter to Jefferson, writing that “without flattery,” the address “adds a Lustre to the whole of your Life if any thing cou’d be necessary to highten your public Character.” He anticipated that any who continued to oppose Jefferson’s administration must see the “soundness of the reasoning, and the temper and philanthropy with which it is express’d,” and it would “have the happyest effect on every person not so vicious as to persist in Spite of Light and truth in a perverse Opinion.” Jefferson replied with appreciation, reiterating to Tyler that “performance” was “the proper office of the second” inaugural, in contrast to “profession and promise” in the first. He also humbly held that he was restricted to “only the most prominent heads” and the “strongest justifications.” He again brought up the defense that he used in Document XII, that “the crusade preached against philosophy by the modern disciples of steady habits” led him to discuss the subject in regard to Native Americans longer “than the subject otherwise justified” (John Tyler to TJ, 17 Mch. 1805; TJ to Tyler, 29 Mch.).

Soon after Americans had a chance to react to the address, European publishers began to circulate the printed speech. By 17 Apr., shortly after the address had reached the frontier of the United States in Louisiana, the London Times printed the full text. Several other newspapers in Britain reprinted the speech. The first paragraph was translated into French and the rest summarized in the Gazette Nationale ou le Moniteur Universel of Paris on 23 Apr. Lafayette commented to Madison that the address had “Speedily Enough Been Received in paris,” and he wrote to Jefferson that it was well suited “to the Wants of this part of the World, and of Course to the feelings of those Who Can not Give Up the Hope of its final Enfranchisement.” He later complained that while the English-language Argus printed the address in full, most Parisian papers “impudently Curtailed and Altered” it. He hoped that a translation that was in progress would be distributed. Pierre Samuel Du Pont de Nemours also read Jefferson’s “admirable” speech in Paris. The address reached William Jarvis in Lisbon, who wrote that it must please any American who “has not the interest of his party more at heart than the welfare of his Country.” He compared Jefferson’s wit to “a new smooth razor, which cuts to the heart before the subject is aware that the wound is inflicted.” But Jarvis cautioned that Jefferson was destroying his enemies “with two & forty pounders” after they had hurled “pellets of mud,” which he feared might “be considered as taking too great an advantage of your superior powers.” Jefferson personally sent Philip Mazzei a copy a few days after the inauguration. Mazzei had already seen a print version from an unspecified Boston newspaper and created a translation. He passed a copy along to Adam Czartoryski in Russia and the prelate Antonio Martini, Archbishop of Florence. Versions of the address were printed in Altona-Hamburg and Cologne later in April, and it was described in additional German-speaking states in the ensuing months (Cunningham, The Inaugural Addresses of President Thomas Jefferson, 97-101; , Sec. of State Ser., 9:276; Margherita Marchione and others, eds., Philip Mazzei: Selected Writings and Correspondence, 3 vols. [Prato, Italy, 1983], 3:384-7; Lafayette to TJ, 22 Apr. and 1 May 1805; Pierre Samuel Du Pont de Nemours to TJ, 23 Apr.; William Jarvis to TJ, 15 May; TJ to Mazzei, 10 Mch.; Mazzei to TJ, 20 July and 12 Sep.).

Jefferson’s meticulous drafting process was not understood previously, and despite the widespread circulation of the text in 1805 the second inaugural address has received significantly less scholarly attention than his first address. Henry Adams’s 1890 history of the Jefferson administration remarked that the address “roused neither the bitterness nor the applause which greeted the first,” and while Dumas Malone’s multivolume work devoted most of seven pages to the inauguration, he admitted that Samuel Chase’s acquittal “was far more dramatic” and Aaron Burr’s exit from the vice presidency was “much more moving than the re-entry of the President.” Jon Meacham tackled Jefferson’s second inauguration in less than a page. The address has drawn more attention from scholars of Jefferson’s public presentation and expression of executive authority, but it remains secondary to his first address. In spite of his laborious attempt to “discountenance” the opposition to “philosophy” and to make a statement about the opposition press, Jefferson recognized, as he wrote in his “Notes on a Draught for a second inaugural Address,” that “the nature of the occasion requires that detail should be avoided.” He used the address to make his case for the performance of his earlier promises and to lay out a foundation for governing performance in a second term (Adams, History of the United States of America during the Second Administration of Thomas Jefferson, 2 vols. [New York, 1890], 1:1; , 5:3; Meacham, Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power [New York, 2012], 408; Jeremy D. Bailey, Thomas Jefferson and Executive Power [Cambridge, Eng., 2007], 213-20; Document XII).

![University of Virginia Press [link will open in a new window] University of Virginia Press](/lib/media/rotunda-white-on-blue.png)